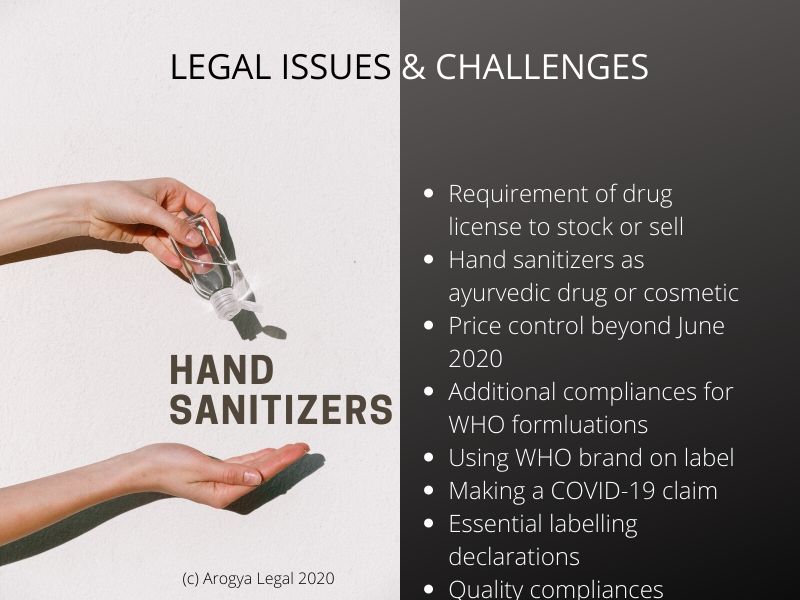

Summary: Due to the sudden spurt of demand for hygiene products due to COVID-19 virus pandemic, several manufacturers and marketers in India are now selling hand sanitizers containing ethanol or isopropyl alcohol as an active ingredient. However, regulatory uncertainties, especially surrounding requirement of drug license for stock and sale and scope of price control are becoming roadblocks for businesses from scaling-up operations. Manufacturers and marketers of hand sanitizers are thus forced to explore alternate options such as manufacturing hand sanitizers as a cosmetic or ayurvedic formulation (Indian medicine) to overcome some of these regulatory challenges. However, these alternatives have their own limitation.

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) has said that hand hygiene is extremely important to prevent the spread of COVID-19 virus. As part of hand hygiene guidelines, WHO has recommended the use of an alcohol-based hand rub for 20-30 seconds using appropriate technique when hands are not visibly dirty. In line with these guidelines, various governments around the world have promoted the use of ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol-based hand rubs for hand hygiene. India is no exception.

The WHO endorsement and government recommendations for alcohol-based hand sanitizers have resulted in high public demand for these products in India. Due to the heightened public demand, there is a race to manufacture and market alcohol-based hand sanitizers (gel) and hand rubs (liquid) (together referred to as “ABHRs”). The Drug Licensing Authorities have also started granting a license to manufacture ABHRs in a record time of three (3) days to drug manufacturers, even to alcohol distilleries and cosmetic manufacturers to ensure steady and sufficient supply of hand sanitizers and hand rubs.

However, manufacturers and marketers of ABHRs are now faced with some legal and regulatory challenges, which they must overcome in order to scale the business of ABHRs. In this article, we have discussed these challenges in detail.

Stock and sale drug license

The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 (DCA) mandates that every drug stocked or sold in India must be sold under a license unless the drug, or the person stocking or selling the drug, is exempt by law from this requirement.

There is no such exemption for ABHRs. Therefore, the entire supply chain, including retailers of ABHRs, are required to sell them under a stock and sale license under DCA.

However, due to COVID-19 (Corona) virus, it is not possible to meet the current demand for ABHRs through existing distribution and retail channels that have stock and sell license for drugs. Therefore, there is a widespread expectation that ABHRs should be sold through general FMCG distribution and retail channels.

The only way to legally do so is by positioning ABHRs as disinfectants. There is an exemption under DCA for disinfectants that allows disinfectants to be stocked and sold without a drug license. Such an exemption from stock and sale drug license is not unique to disinfectants. Several other drugs presently enjoy such exemptions as well, for example, oral rehydration salts, medicated dressings, condoms etc.

Some courts in India have, in the past, recognized the disinfectant properties of specific formulations of antiseptic liquids containing alcohol and validated their ability to avail exemption from drug stock and sale license otherwise available only to disinfectants. However, the courts are yet to specifically opine on exemption of ABHRs in general from the requirement of stock and sale license.

The industry is awaiting an official clarification on this issue. The central drug regulator, the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI), is currently reviewing the regulatory positioning of hand sanitizers, including ABHRs, as ‘disinfectants’ and availability of exemption from drug stock and sale license to them. Until DCGI takes a final position, some State-level Drug Licensing Authorities may accept ABHR’s claim of disinfectants and allow them to be stocked and sold by the distributors and retailers without drug license. But Some State-level Drug Licensing Authorities some may not do the same, and the overall objective to scale ABHRs business to meet demand may not be met.

It is our view that such an exemption should be available to ABHRs, especially since the US Pharmacopeia, which is one of the pharmacopoeias recognized under Indian law for drug quality standards, explicitly acknowledges disinfectant properties of ABHRs.

Meanwhile, with a view to improve access to ABHRs, the Government has notified them as an essential commodity (discussed in next paragraph in detail). However, notification of ABHRs as an essential commodity does not automatically exempt them from the requirement to be sold under a stock and sale drug license either at distributor or retail level. All drugs sold in India are, in fact, essential commodities.

To overcome the limitation imposed by requirement of drug stock and sale license on distribution of ABHRs, some manufacturers and marketers are manufacturing ABHRs under as an ayurvedic drug that is made under an ayurvedic drug manufacturing license, or as cosmetic that is made under a cosmetic manufacturing license. Both ayurvedic drugs and cosmetics do not require any regulatory license for stock and sale and therefore may be distributed via a supply chain that does not have a drug stock and sale license.

However, there are significant challenges in selling ABHRs as ayurvedic drugs or cosmetics. For example, ayurvedic drugs containing alcohol have a long history of litigations with excise department for their potential to be abused as intoxicating liquor. Some State Governments in India have prescribed a limit on alcohol content, stating that alcohol used in the manufacture of antiseptic solutions should not contain alcohol in excess than is necessary for the preservation of (ayurvedic) ingredients. As ABHRs typically have 60%+ alcohol content, manufacturers and marketers of ABHRs must ensure that their product passes the above test.

When ABHRs are sold as cosmetics, it is not possible to make any ‘drug’ claim on it. For example, it is not possible to claim on the label that the ABHR ‘kills’ germs, as it would mean that the product is not for cosmetic application but for medicinal application. The definition of ‘drug’ under DCA is broad and covers all substances that are intended to be used in the prevention of disease in human beings. If any such ‘drug’ claim is made on the label of a cosmetic, then it may invite strict regulatory action under DCA.

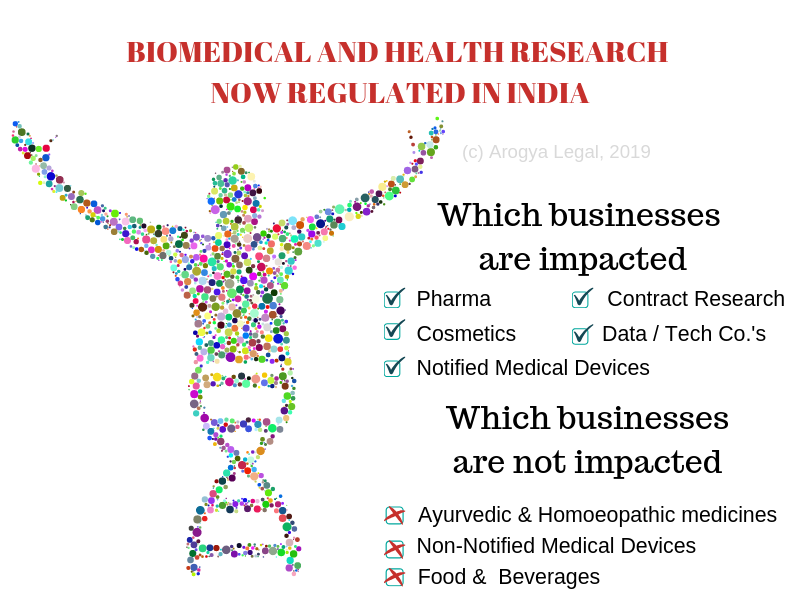

Status as new drugs in India

The two ABHR formulations recommended by WHO are: Ethanol 80% (v/v) or Isopropyl alcohol 75% (v/v), Glycerol 1.45% (v/v) and Hydrogen peroxide 0.125% (v/v). As per the records released by central drug regulator, DCGI, both these formulations were first approved for sale in India in 2017. These formulations now preferred by most manufacturers and marketers due to the WHO endorsement and constitute the bulk of new ABHRs being launched in India.

Under New Drugs and Clinical Trial Rules, 2019 (NDCTR), a formulation is deemed to be a “new drug” for four years from the date of its first approval. Therefore, both WHO recommended formulations are to be currently treated as ‘new drugs’ for regulatory purposes in India until 2021.

When any drug is classified as a ‘new drug’, it has two consequences for the manufacturer of the drug. Firstly, a prior permission from the central drug regulator, DCGI, is required to be obtained in addition to a manufacturing license. Secondly, after the manufacturing license is granted, the manufacturer is supposed to undertake post marketing surveillance and submit periodic safety update reports (PSURs) to DCGI.

The manufacturers of ABHRs as per WHO recommended formula must ensure that DCGI permission is in place for their products, in addition to the manufacturing license, and must make periodic submissions of PSURs to DCGI as per the format specified under NDCTR.

Price control of hand sanitizers

ABHRs manufactured under a drug manufacturing license have always been under some or the other form of price control. The Drug (Prices Control) Order, 2013 (“DPCO”) regulates the prices and distribution of ABHRs containing ethyl alcohol 70% (v/v) since 2013. The current price ceiling on 70% ethyl alcohol solution is 0.56 Rupees per ml, which translates into 112 Rupees for 200 ml. All other ABHRs are restricted from increasing their maximum retail price by more than 10% in between twelve months.

However, as described earlier, it is possible to manufacture “hand sanitizers” as an Indian medicine (ayurvedic drug) or cosmetic as well. Ayurvedic formulations are not regulated for price by DPCO to a great extent and cosmetics are not regulated for price at all. Thus, the price cap of 112 Rupees for 200 ml will not apply to ayurvedic or cosmetic hand sanitizers. Furthermore, DPCO does not regulate cost of raw materials of drugs, in this case methylated industrial alcohol / denatured ethyl alcohol / isopropyl alcohol. The DPCO also does not empower State Governments to direct manufacturers of drugs to enhance production capacity and increase their availability. This power is vested only with the Central Government.

In order to overcome these challenges, the Indian Government has notified The Essential Commodities Order, 2020, thereby classifying “hand sanitizers” as essential commodity until June 30th, 2020. Due to this, all hand sanitizers (drug, ayuvedic medicine, cosmetic) and the raw material used in them have come under the purview of price control and have become amenable to jurisdiction of respective State Governments. The Indian Government has also notified The Fixation of Prices of Masks (2 ply and 3 ply), Melt Brown Non-Woven Fabric and Hand Sanitizers Order, 2020 (“Hand Sanitizer Price Control Order”). As a consequence, all hand sanitizers (drug, ayurvedic, cosmetic) cannot be sold for price higher than 100 Rupees for 200 ml until June 30, 2020. Needless to say, after expiry of the aforesaid order, hand sanitizers will be regulated as per DPCO (to the extent applicable to them).

There has been a collateral impact of the Hand Sanitizer Price Control Order on non-alcohol based hand sanitizers. There are currently at least twenty-four (24) formulations of hand sanitizers approved for sale in India, some of which are not alcohol-based. The Hand Sanitizer Price Control Order does not clarify whether it applies only to alcohol-based hand sanitizers or other hand sanitizers as well. The expression “hand sanitizer” is not defined under law, and has been interpreted loosely by the central drugs regulator, DCGI. The DCGI has in fact put out a list of all hand sanitizers approved by it which includes both alcohol-based and non-alcohol based hand sanitizers. Therefore, there is a risk that the Hand Sanitizer Price Control Order may be interpreted broadly and cover non-alcohol based hand sanitizers as well.

On a separate note, manufacturers who have been selling formulation of ethyl alcohol 70% (v/v) will have to obtain a prior price approval from central price regulator, National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA), before manufacturing ABHR containing ethyl alcohol as per the procedure prescribed under DPCO.

Making Corona related Claim

There is scientific laboratory data now in place to support the claim that WHO recommended formulae for ABHRs, or ethyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol in concentration of more than 30% v/v, can inactivate COVID-19 virus in thirty (30) seconds.

However, such scientific laboratory data has not been endorsed by India’s central drug regulator, DCGI, and is very specific to WHO formulations when used under laboratory conditions. If any manufacturer or marketer wishes to put a generic COVID-19 virus related claim on its label, it may need to first obtain prior permission from DCGI who may decide to treat the ABHR as a untested ‘new drug’ and require the manufacturer to submit supporting laboratory data for its own formulation before it is permitted to make any COVID-19 virus related claim.

Needless to say, in absence of the permission from DCGI, any such claim may make the manufacturer liable for prosecution under DCA.

Making “WHO recommended formula” claim

There is an expectation in some quarters of the industry that the if an ABHR is manufactured as per the WHO recommended formulae (described in earlier paragraphs), then it should be launched with a supporting claim of ‘WHO recommended formula’ on its label. However, it may not be ethical to commercially exploit the WHO brand name since the WHO formulae were originally recommended as an alternative when suitable commercial products were either unavailable or too costly. The actual recommendation from WHO for ABHRs is, in fact, for any effective alcohol-based hand rub product that contains between 60% and 80% of alcohol.

For context, the WHO recommended formula even today is intended for local production by pharmacies and WHO has permitted use of its brand name by them in order to (most likely) lend credibility to the end product.

On the same note, it is an offence in India to put the name of World Health Organization or its abbreviation (WHO) without prior permission of the Central Government under the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Improper Use) Act, 1950. Therefore, even if a manufacturer is able to manufacture the exact formulation as recommended by WHO, it should not claim that it is manufactured “as per WHO recommended formula” without prior permission of the Central Government.

Putting Government Logo for endorsement in fight against Covid-19 virus

Like World Health Organization, putting the name or official seal or emblem of the Government of India or of any State or of a Department of any Government without prior permission of the Central Government is an offence under the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Improper Use) Act, 1950.

Getting the labelling right

Apart from alcohol, there may be other active ingredients in ABHRs such as hydrogen peroxide which kill or limit the growth of harmful microorganisms. Such ABHRs with more than one active ingredients fall in the category of ‘fixed dose combinations’ (“FDCs”). Every FDC is required by law to state the composition on the label first, followed by its brand name. For instance, in case of the WHO recommended formulae described earlier, the name of the active ingredients must appear prominently on the label and simply writing “hand sanitizer” or “hand rub“ may not be enough.

Further, due to the high alcohol content in the ABHRs, there are specific declarations that ought to appear on their label. Each label must specify that ABHR contains denatured alcohol (in case of use of methylated spirit) and that it is for external use only. If the ABHR is making a disinfectant claim, then it must specify the mode of use. The content of the alcohol in the ABHR must be stated in terms of average percentage of absolute alcohol.

It is also advisable to write about storage conditions and appropriate warnings, in view of the high concentration of alcohol in ABHRs.

Same brand name, different drug

Some marketers of ABHRs are selling two or more formulations of ABHRs under the common / umbrella branding of ‘Hand Sanitizer’. This strategy should be revisited, since different formulations of ABHRs are different drugs, and selling different drugs under a common / umbrella branding of ‘Hand Sanitizer’ may be misleading.

If a marketer is selling ABHRs manufactured under pharmaceutical drug license and ayurvedic drug license under a common / umbrella branding such as ‘Hand Sanitizer’, then the regulatory risk identified above may increase since pharmaceutical drug and ayurvedic drug are two very different products though with the same end-application.

The law does not want consumers to be misled while buying drugs. Therefore, every manufacturer who wishes to sell ABHR under a brand name is required to file a declaration at the time of applying for drug manufacturing license. The declaration states that the brand name under which the drug is proposed to be sold is not used by any other manufacturer. This declaration should be submitted by manufacturers of ABHRs before obtaining the manufacturing license for ABHR.

Getting quality aspects right

The manufacturers of ABHRs is obligated by law to ensure that its products are of standard quality. The WHO has recommended that the efficacy of any ABHR should be proven according to European (EN 1500) or American (ASTM E-1174) standards. Considering these are foreign standards and may not be enforceable in India, manufacturers of ABHRs must ensure that the hand sanitizers at least satisfy requirements of quality and efficacy as per applicable Indian standards.

As of date, in case a drug is found to be not of standard quality (NSQ), the liability lies with the manufacturer and not the marketer. However, this will change in future. From March 1, 2021, the marketers of drugs themselves will be responsible for the quality of the drug and the agreement between marketers and manufacturers will play an important role in the determination of liability. Therefore, the meeting of applicable Indian quality standards by ABHRs will be important for both the marketer and the manufacturer.

Conclusion

Hand Sanitizers, specifically ABHRs, are more relevant and in-demand in India than ever before. However, manufacturers and marketers of ABHRs should be careful about compliance with laws and regulations, because any oversight today may invite strict regulatory action in future.